On September 2nd, 1974, a large group of Americans from Boise, Idaho, arrived in Oñati, led by Professor Pat Bieter, with the aim of spending an academic year in that town in the Basque province of Gipuzkoa.

The group was not exactly homogeneous, because many of them were young descendants of Basque emigrants, although not all of them were, nor were they all from Idaho. For this reason, not everyone had the same motivation when it came to undertaking a whole course in a country like Spain during a dramatic time and in the tailwinds of the Franco dictatorship, with an added tension in a Basque Country that, in addition to fighting for democracy, was doing so for the recovery of its freedom as a nation and the survival of its language, its culture and its identity. Furthermore, in a Basque Country where ETA, an armed organization that had begun 15 years prior, was acting with force.

There were precedents of previous summers, when other smaller groups made stays in the Basque Country, with similar objectives but were reduced to a few weeks. These stays were fundamental for the definitive step towards the creation of a much more ambitious program from 1974 on.

All this took place in a unique context. On the one hand, the Basque diaspora in the United States was immersed in a process of transformation in the 70s in which the classic folkloric activities, gastronomic and even charity activities had not been replaced but complemented by new priorities such as political demands about what was happening in the Basque homeland, especially in the provinces on the Spanish side, or the learning of euskera (the Basque language) by the new generations. Milestones such as the creation of NABO (North American Basque Organizations) in 1973 or the birth of Basque Studies programs in Reno and Boise were no strangers to this process of change.

That adventure (a term still used today by its protagonists) was a bit of a voyage of discovery. The group was heading to a Basque Country in a full blown political and social boiling point, and to a country in full dictatorship. It was a journey of conflict, of discovery, of becoming aware, of reunion, of returning to origins. And it was also the beginning of many things: the beginning of bonding that has endured despite distance and time gone by; the beginning of relationships that ended up in families; a beginning for locals to see the American diaspora in another way, and for visitors to know the Basque Country in new way, whether or not this was the land of their ancestors. There is an image that the protagonists of that time frequently remember and that perfectly reflects the fullness of the experience that academic year: the members celebrated a baptism, a first communion, a wedding and a funeral during that unique time.

However, the beginning was an unexpected one, with the group arriving to Oñati escorted by the Guardia Civil (one of the Spanish police forces), due to the stir that had been created in the town by their arrival, and actually, throughout the Basque Country. Certainly, a sector of the population viewed this major arrival with reluctance and there had been a lot of rumors about the real reasons for their stay in Basque lands. Tension had reached such an extent that a few days before their arrival, an armed group planted a series of bombs in the facilities that were to house the new guests.

The Protagonist

To begin with, despite what we have been able to hear and read about on numerous occasions, we must affirm that it was not ETA who planted those bombs, but rather an armed group popularly known as Los Cabras (the Goats), for being led by the former leader of ETA Javier Zumalde, El Cabra (The Goat).

El Cabra (Amorebieta, 1938) is a Biscayan with origins in Oñati who in the beginnings of ETA, already in its 4th assembly held in 1965, had been appointed head of the military framework of the armed organization. His interest in weapons and guerrilla warfare made him the right person for it, although it should be remembered, to have a clear picture of what ETA meant at that time, that the first death caused by armed activity did not come until a few years later. Their actions at that time were limited to blowing up equipment such as television transmitters, placing Ikurriñas (Basque flags) and similar sabotage.

There were several circumstances that made the commands organized by Zumalde acquire a certain autonomy over time, until from 1966, they operated under the new name of Grupos Autónomos de ETA (Autonomous Groups of ETA). Its activity was developed mainly in the valley of the Deba river in the province of Gipuzkoa and in the Duranguesado of the province of Bizkaia, both adjoining regions. All this until the fall of 1968 when most of its members were imprisoned or were forced to go into exile.

Already in exile in Iparralde (The Northern Basque Country), Zumalde dedicated himself on one hand to collaborating with ETA, but also to rebuilding his own groups, which would begin to act in that new era under the name Resistencia Vasca (Basque Resistance). It is precisely these groups that placed the bombs in the seminary of the Augustinian Fathers where the American delegation was going to set up its campus.

It was Zumalde himself who in an autobiography wrote about, and justified, such actions in a chapter with a very eloquent title: “Our very own war with the CIA.” The chapter explains many things, including the story of the expedition of the commando that left from Hendaya of the Northern Basque Country to commit the act. Zumalde also tells more interesting details under the title Operation Boise. He explains about the reports that were coming to him from Oñati about the Americans, reports prior to the arrival of the group, but also throughout the course of their stay. All of them give an idea of what prompted El Cabra to materialize this action, but they also contribute to understanding what part of the population of Oñati in particular, but of the Basque Country in general, was thinking at that time. Certainly, some details of those reports have become comical over time.

The Bombs

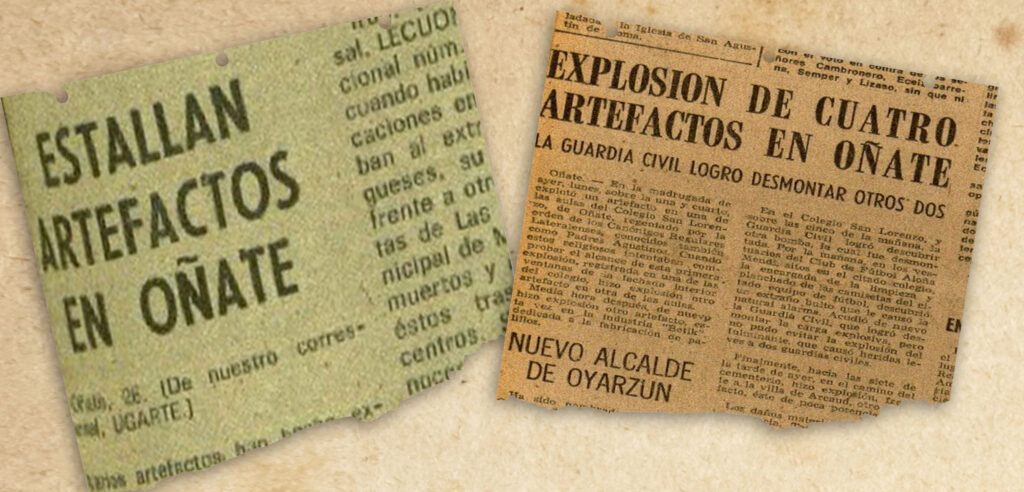

The bombs exploded in the early hours of August 26, 1974. There were six bombs planted, but only four went off. El Cabra and his command also took the opportunity to place another explosive in the local toothpick factory of Betik, immersed at that time in a labor conflict.

Summarizing his extensive story, Zumalde explains that the commando left Hendaya on a ship guided by an old arrantzale (sailor) from Iparralde (the Northern Basque Country). There were three men, each carrying a pistol, three ammunition magazines and six hand bombs. The boat arrived to the island of Izaro (province of Bizkaia) and from there to the beach of Ondartzape of Mundaka, in a raft that they had brought. He says that from there they were transferred to Larrea (province of Araba) to cross the mountainous terrain to Oñati, taking refuge in a kind of cave. After a few days, they proceeded to place the six explosives weighing one kilogram each, with timers set at different times so that the explosions would be gradual. Zumalde seemed very interested in providing the data of the weight of the explosives to emphasize that the objective was not to destroy the building of San Lorenzo that was going to house the Americans, but rather to create “confusion and chaos”.

Clearly, these bombs did not meet the objective they set out to, because they didn’t create much confusion and chaos. The Basque media barely offered a few brief paragraphs in lower exposure print locations. On August 27th the newspapers reported very briefly on the placement of the explosives at the Augustine’s San Lorenzo seminary and at the toothpick factory, but they did not even tie the event to the arrival of the Americans, we do not know if it was due to ignorance or the result of a premeditated decision to silence the pretensions of the commando.

The Previous Campaign against “Intruders”

Although it seems paradoxical, and it is thought that an attack with explosives is always more significant because of its severity, in general, these bombs caused less impact than the previous campaign. This effort against the incoming Americans was put in place a few years earlier when a Colegio vasco-americano (Basque-American School), as they called it, was going to be organized in Oñati.

Indeed, what Zumalde calls in his book the first phase of Operation Boise was more successful, which consisted of generating an environment in the town against the arrival of those he described as “intruders”. In fact, it would be incorrect to give all the prominence of such a campaign to the so-called Basque Resistance, since there is no doubt that also in other sectors of the municipality (and throughout the Basque Country) there was enough distrust towards the novelty that the arrival of the large delegation represented.

But why did the armed group and its supporters undertake this effort with such intensity against the Americans? The truth is that it’s quite embarrassing to read his explanations now, especially considering that the autobiographical book Zumalde which we’re referring to was written in 2004 and that he had plenty time to realize how wrong he was as well as how mistaken his accusations which he made against people of recognized prestige were. But let’s get to it.

The Story

El Cabra says that he and his colleagues had been receiving reports from the Local Resistance for a year that said that the CIA intended to create a base in Oñati with a program developed and organized by Jon Bilbao, an alleged agent of the agency. Interestingly, Zumalde himself had maintained a very fluid and friendly relationship through correspondence with Bilbao for some years. He adds that Bilbao stopped going to Oñati in 1973 because he had already been exposed, and that he was replaced by Selma Huxley, a prestigious Canadian historian, much loved in the Basque Country, especially in Oñati, where she had been since 1972, drawn by the historical archives that she needed for her research found at the ancient university of that town. It is a very surprising accusation, since he adds that a very confidential folder on clandestine and subversive political activities of Basque groups and parties was intercepted from her.

The plan was first of all to fill the town with leaflets and communiqués, and other methods of action, and once the tone was set, to move into direct action by placing the explosives. All this, because in his opinion, the group of young Americans about to arrive would be the cover for the missions of additional CIA agents who would soon be arriving.

Conversations and Negotiations

As Pat Bieter continued with the preparations, his concern grew as the date of September 1974 approached. And all because he was aware that an opposing environment had been created, a very strange climate which extended way past El Cabra’s immediate circle, even reaching prominent political personalities of the time.

The correspondence between Pat Bieter and Father Benito Ijurra and Father Francisco Lasa, who were responsible at that time for the Augustinian community of Oñati, is a palpable example of the tense climate that was experienced in the months prior to the arrival. The owners of the campus did not hide their state of anxiety, because they had learned that Bieter had gone to Iparralde (the Northern Basque Country), supposedly to negotiate with the exile about the arrival of the group. The Augustinians therefore threatened to break the agreement if they were not informed about what was happening. They received explanations that reassured them in part, but the tension continued. Professor Bieter clarified to them that his relations with Iparralde (the Northern Basque Country) dated back to 1972 and there was nothing to hide.

In reality, representatives of the Basque exile of 1936 like Telesforo Monzón and the first generation of ETA exiles such as Juan Jose Etxabe were sympathetic and in solidarity with those who opposed the arrival of the young Americans, that is why this discrete diplomatic effort was undertaken in which personalities like Txillardegi also intervened, who had been one of the founders of ETA, although he no longer belonged to the organization. There was constant exchange of letters, some of them very harsh, and the testimony of some participants in those conversations show that the pressure was very intense, even with recommendations that the campus project be suspended.

The Echoes of the Controversy

The fact that the international press echoed the conflict didn’t help to calm tempers much either. In a surprising report in the French newspaper France-Soir, the journalist and writer Roger Colombani told a convoluted story of arms trafficking, espionage and kidnappings in which the Oñati Campus acquired a stellar role. Interested in the issue, the influential Spanish weekly Cambio 16 sent a reporter to the Basque town in February 1975. After learning about the experience in situ and maintaining direct contact with Professor Bieter and other campus officials, he concluded that it was all a ridiculous hoax. The journalist even transcribed a phrase that was ironically released by one of the students he interviewed: “We have actually come to steal the chocolate recipe.” It should be explained that Oñati has historically been a large chocolate producer with many factories dedicated to chocolate production.

That phrase caused quite a stir at that time and shows that there was no longer any concern about what had happened during the previous months. The group’s integration in the Basque Country was magnificent and the experience was unforgettable. However, there are those who, even years later, drew from all of this a surprising conclusion in the least, and even delusional. Here was Javier Zumalde’s, El Cabra’s thought: “We didn’t manage to beat the Great American Nation, but we won the game and ended their plan to install a base for Intelligence in Oñati.”

Author’s Note: This article is a brief summary of one of the chapters of the book that is being written about that experience, and that is part of a broader project which also includes a documentary, an exhibition and the acts of commemoration of the 50th anniversary, to be held beginning September 2024.

Excelente y exhaustivo reporte de lo que pasó. Buena narración y ajustada a a realidad cien por cien. Me tocó vivir la experiencia, ya que estaba en el Colegio San Lorenzo en esos años

Hola Patxi, ?Cuanto tiempo? ?Por donde estas? He pensado mucho en ti estos anos.

Me encantari visitarte uno de estos dias.

Un fuerte abrazo,

Carmelo Urza

curza@unr.edu (775)830-2680

Oso interesgarria. Zerbait jada irakurrita nuen, uste dut zuk zeuk idatzita, baina orain zabalagoa.

Yo soy periodista Americano de Idaho. Estuve con la 1974-1975 aventura BSU en Onati. Y regrese a vivir in Donosti 1977-1979. Me encanta el articulo sobre “Bombs in Boise”

Aprendi por leer lo mucho sobre como llegaran los explosivos a San Lorenzo….y sobre la tension que existia antes de la llegada de los estudiantes Estadounidenses a Onati. He tenido muchas experiencias come periodista pero Onati fue el comienzo de todo para mi. Gracias por el peridismo sobre aquellos anos unicos.