by Felix Maraña.

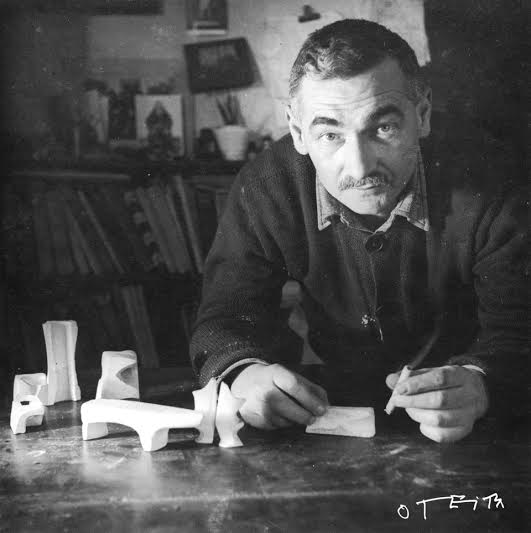

Ten years have gone by since Jorge Oteiza’s passing (1908-2003), sculptor, poet, thinker and social critic, born in Orio, a small Basque coastal fishing village. Oteiza is one of the most illustrious Europeans of the artistic avant-garde and time has given him a place in the history of contemporary art celebrating his talent. Yet, his representation in his beloved province of Gipuzkoa still remains to be settled, where a place is lacking for encouraging the awareness of his work and the study of the projects devised to shake the cultural desert during Franco’s dictatorship. His critical intervention and his solvent thought stirred up a bleak political and cultural environment in the 1960’s.

Oteiza donated all his documentary and artistic legacy (what he owned in 1992) to Navarre, a sister land. The Museum Foundation that bears his name in Altzuza (a small village near Pamplona) was opened days after the death of the Basque sculptor. This museum should be the principal reference, because Oteiza wanted it that way. However I do not think that it would be inconvenient for an extension of his memory that, as Picasso has several museums in the world for example, Oteiza benefited from an additional space, corner or laboratory where his thought and intellectual view could be shared rigorously and with enthusiasm. Oteiza was not only a sculptor who received the first prize of the International São Paulo Biennial (1957), but an intellectual who intervened in a manner determined for the renewal of culture, making his behavior an example of how an artist should go beyond his own work, dissolving into the needs of his country. “We belong to a country as long as we feel the need of serving it,” he wrote.

In other words, Julio Caro Baroja (1914-1995) explains, affirming that Oteiza is not only an artist but a memory. As he puts it: “Memory is everything that, once noticed, tells us much more about what we are, helping identify us and ratify what we are. With Oteiza, mistaken or not, I see a man of the Basque Country more authentic and whole, expressing himself without fuss or deception. In the end, men like him bring us closer to the humanity of our elders. This man also has a historical sense, something that not everyone has, and he has that enviable strength of one who beyond thinking and feeling, acts. He is the type of Basque who is unwilling to stand still and intervenes.”

Therefore, I understand that the issue is unsettled as to what the representation of his work and the memory of his civil character is to be in places like San Sebastian and Gipuzkoa, the city in which he lived during childhood, and the territory where he produced his main artistic and cultural creations like the statues of the basilica of Arantzazu, where the language of modernism was applied to religious spaces. From 1954 to 1974, Oteiza resided in the city of Irun, where he writes the book Quousque tandem…! (1963) and the basis of the essay Spiritual exercises in a tunnel, whose first edition appeared in the Northern Basque city of Bayonne (1983). In fact, its foreword is dated in Irun, on July 14, 1963, half a century ago. Exercise number two in this book stands out, “At this time for a popular revival of the poet and the Basque artists,” a true discourse on poetics by Oteiza. In this text Oteiza says: “In all languages, we die when we remain silent.”

In 1963 in Bayonne, Oteiza met André Malraux, France’s Minister of Culture, to propose the creation of a Center of Aesthetic Research in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, a coastal town in the Northern Basque Country. That same year he announced his entrance to film in the magazine “Noray”, and promoted the development of projects that marked successive milestones in Basque culture, and among others: Contemporary Art Week in Irún (1961), the musical group Ez dok amairu (1965), the exhibition of the group Gaur of the Basque School (1966), the film Ama Lur (1968), the statuary of the Apostles at Arantzazu (1969), the preparation of the Deba School Project (1969), the stele of the new international Bidasoa bridge (1971), meetings in Pamplona (1972), the Oteiza Exhibition in Txantxangorri Gallery (Hondarribia, 1974). After this exhibition, Oteiza moved to Altzuza, where his Museum is currently located, inaugurated ten years ago to transcend him.

But Oteiza extended much further beyond his own Basque Country. Intellectuals such as José Manuel Caballero Bonald, just to mention one testimony, corroborate. In 1999, Caballero writes: “Within these advanced aesthetics for half a century, Oteiza was already a maestro, a driver who at times was very present and sometimes voluntarily distanced. Intelligent, impertinent, incorruptible, chaotic (in a way), possessing, in a superlative degree, a vibrant ability to blend passion and knowledge. Even more than his sculpture work (with all his highly personal expressionism leading to abstraction), what really attracted me was the personality of Oteiza as art theoretician, as aesthetic analyst and (more than anything perhaps) as a cultural critic. He was driving very unique concepts and was a great subversive… I learned a lot listening to him discussing with Viola or Moreno Galván (two other extremely intuitive individuals) and it always seemed to me that aesthetic issues that would have been improbable in any cultural environments of Madrid, mostly brought on somewhere between imaginative anemia and backward hunger, were raised there.”

Ingenuity of a universal Basque, Jorge Oteiza, who believed that art could not change the world, but that the world could only be changed by those people whom, previously, art had changed. Such was his faith in the saving power of artistic creation, in the transformative validity of art in the history of the world.

|

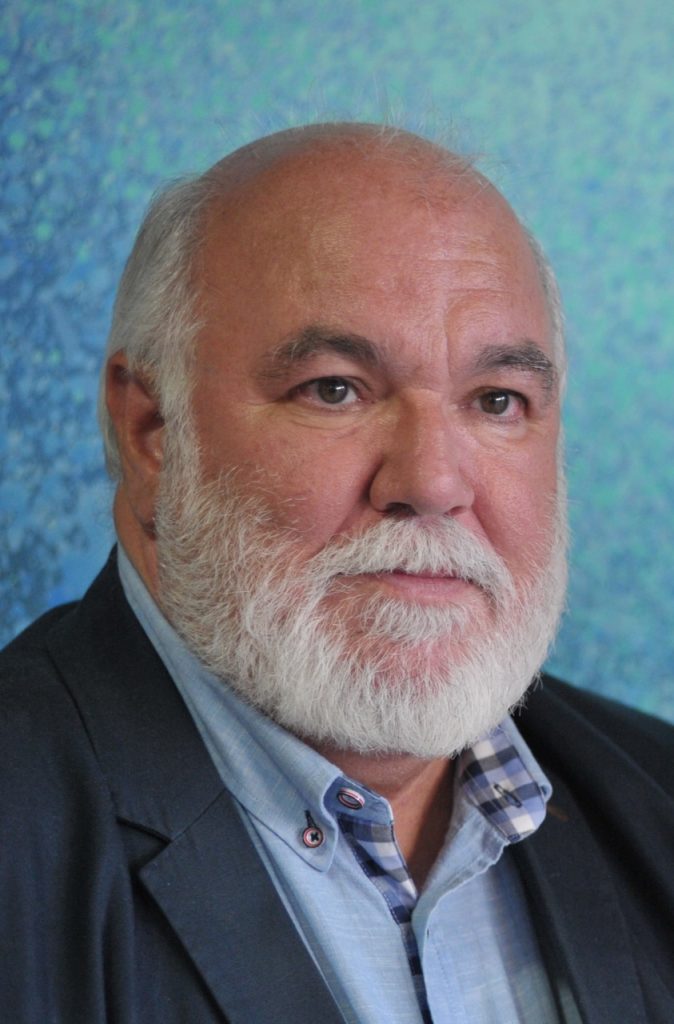

Félix Maraña is a journalist, writer and editor. |

| kurpilfe@hotmail.com | |

| www.berminghamedit.com/ |

Be the first to comment on "Jorge Oteiza – the Solvent Artist"