by Aingeru Epalza.

Euskalerria Irratia, like the rest of the radio stations in the vicinity of Pamplona, capital city of Navarre, runs morning, afternoon and evening programming. It offers news, magazines, interviews, musical programs and weekend broadcasts of live matches of Osasuna (the Navarre team in the first division Spanish football league). However, Euskalerria Irratia has two differences compared to other radio stations. First, it broadcasts in Basque. And second, Euskalerria Irratia is a radio station running without legal permits.

Euskalerria Irratia has been around for some time. It just turned 25 years without missing even a single day on the air waves. In this quarter of a century the Government of Navarre has denied licensing on three occasions. Judges have ruled in favor several times, but the Government of Navarre has always found a way to continue denying the license. Reasons argued are always technical. However, everyone knows that if it broadcast in Spanish it would have been granted its license long ago. Nevertheless, despite prohibitions and fines, Euskalerria Irratia has continued broadcasting from the Irrintzi Tower in Pamplona.

The team at Euskalerria Irratia radio station in Pamplona

What is happening with Euskalerria Irratia is a direct reflection of the politics of the Navarre Government regarding the Basque language. And this policy is evident, above all, in the media field. The Navarre Government has also created obstacles for the television stations of Euskal Telebista broadcast from the Basque Autonomous Community. The Basque-speaking children of Navarre, nowadays, cannot see cartoons in their language. Their Government prevents it. And this is happening in a Democratic Western Europe, in the 21st century.

The Shadow of the Gaelic

The history of the Basque language in Navarre can be compared with the Gaelic in Ireland. Until the end of the 18th century or early 19th, the Basque language was the majority language of the territory. However, it was not the language of those in power. They spoke mainly in Spanish even when Navarre was an independent Kingdom, and even more so since it was conquered by Spain in the beginning of the 16th century. Thereafter, for centuries, marginalization policies established from the cores of power have led to the decline of the language.

At the beginning of the 20th century, only 25% of the people of Navarre spoke Basque. The prohibitions of the Franco dictatorship accelerated the descent. In the 70’s knowledge of the language was below 10%. The majority of Basque-speakers were also farmers or lower class workers, relegated to small towns in the Northwest of the territory, and elderly people in most cases. In almost all situations the chain of transmission to new generations had already been broken.

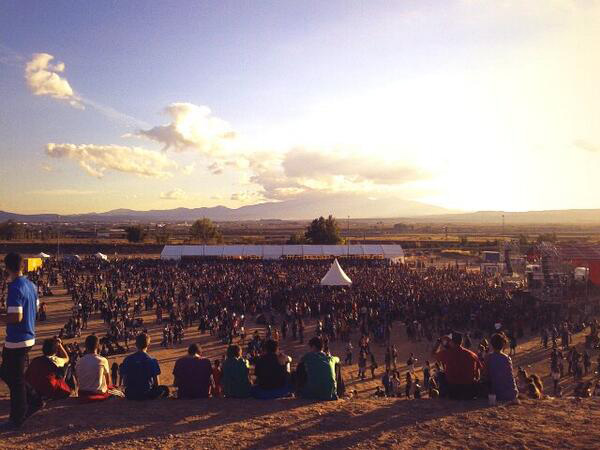

“Nafarroa Oinez 2013” in Tudela (Celebration for Basque schools of Navarre)

First attempts at recovery of the Basque language in Navarre date back to the late 19th century. In the 20th century, there was certain prosperity during the second Spanish Republic (1931-36). Following the subsequent collapse, a renaissance occurred in the 1960s, with a modest beginning, which then took on some momentum after the end of the dictatorship. As in the Basque Autonomous Community, Basque schools for the education of children in the Basque language have also been created in Navarre. Likewise, night schools and euskaltegis have been launched to promote adult literacy. Radio stations, publications and even some local television stations have also been created. And as a result, a cultural movement has emerged that has helped develop writers, journalists and other serious artists. However, all of this has developed without the help of Navarre institutions, unlike in the Basque Autonomous Community.

Policy of Neglect

Due to historical reasons, social support for the Basque language has been weaker in Navarre where political “basqueness” has not been the majority either. After Franco, Navarre was organized into a one-province Autonomy within the autonomous communities of the Spanish State. A portion of the citizens wanted unification with the other three Western Basque provinces, but the political forces in power imposed their own will: PSOE (Spanish Socialist Party) and UPN (Navarre regionalist, and pro-Spanish State, right wing party). PSOE ruled Navarre throughout almost the whole decade of the 1980s. UPN has dominated Navarre during the last two decades, almost always with the support of the Socialists. Both of these parties have insisted on neglecting and alienating the key emblems of Basque identity.

Under the legislation approved by the majority of the Parliament of Navarre during these years, Basque as an official language is only recognized in the Northwest of the territory. Today, however, the majority of the Basque-speaking Navarrese is urban and middle-class and resides both in the capital of Pamplona as well as in the surrounding villages. It is precisely there where the management and main services of the autonomous community are located. However, in this area only a few language rights are recognized. In the South of the territory, on the other hand, none are recognized at all.

During the past 30 years, the relationship between key institutions of Navarre and Basque-speakers has varied. There were some good moments when Juan Cruz Alli was the President of Navarre. Yet, from the year 2000 to now, under the presidencies of Miguel Sanz and Yolanda Barcina things have deteriorated significantly. Taking advantage of the stigma that the actions of ETA left in the Basque-speaking population, UPN has converted the Basque language into its enemy, putting stifling and prohibition policies in place. Now, in the year 2013, ETA has silenced weapons and ended its attacks, but this Party has not changed its policy against the Basque language at all.

Among the supporters of this language in Navarre we find people of all walks of life, rich and poor, urban and rural, left and right. Everyone, however, seems to agree on one aspect: the “sine qua non” condition for the Basque language to survive in Navarre is a shift of the electoral map, removing UPN from governing power.

|

Aingeru Epaltza is a writer and journalist. |

| aingeruepaltza@gmail.com | |

Brilliant article. Thank you for giving some light about the Basque language in Navarre.