This past April 8th there was an event of great significance in the history of the Basque Country: the disarmament of ETA. This historic day, which was announced weeks in advance and prepared with great attention to detail, had many political and social agents involved as protagonists.

The self-proclaimed peace artisans turned over to a representation of the International Verification Commission (IVC) the geolocation of eight “zulos” (underground caches), as well as a list of weapons, explosives and detonators that would be found in them. Along with Txetx Etxeberri, representative of the artisans and Ram Mannikalingam, the representative head of the IVC, Mateo Zuppi, Catholic Archbishop of Bologna and Harold Good, a member of the Methodist Church of Ireland, who had already participated in the process of disarmament of the IRA, served as witnesses at this event. The Mayor of Bayonne (the city hosting the event) also played a special role, as well as the President of the newly created Community of the Northern Basque Country, Jean-Rene Etxegarai. A few hours earlier, in a statement sent to the BBC, ETA had already declared itself a “disarmed organization”.

The Precedent: Aiete Peace Conference in 2011. El Diario Vasco

Later on, 172 representatives from civil society went to the designated locations and witnessed the collection of weapons by French police officers. After the disarming ceremony that morning, the city of Bayonne drew thousands of people together that afternoon who celebrated the disarmament and listened to the manifesto that the peace artisans prepared for the occasion which proposed new steps that, in their opinion, should be taken for reconciliation in the future.

Although the vast political and social majority of the Basque Country saw what was happening during the historic day as great news, there was certainly not such consensus when evaluating the method chosen for the presentation of the disarmament, which for certain sectors had excessive paraphernalia and dramatization and should have been handled in a more discreet manner. At the base of this discussion, the dialectic battle over ETA’s ending emerged once again: at one extreme, the Organization and the people somehow related to it, who referred to it as turning over the weapons to the people from whom they had taken them decades ago; and the other extreme, those who talked of defeat and surrendering; and between the two poles, dozens of varying perspectives.

This is what took place on a day of disarmament which, actually, was the third attempt to make it happen. In fact, in January 2014 there was a symbolic act before the IVC, advertised through a video, but considered a failure and hardly credible. On the other hand, in December 2016, in the town of Luhuso (province of Lapurdi), the French police aborted an attempt for the disablement of weapons by the peace artisans, who were arrested. Through this act the group was made known, who four months later would lead the definitive disarmament. The broad social support that their willingness to collaborate in the disarmament brought and the almost unanimous petitions for their release from prison were key factors for continuing with their efforts.

In addition, during the previous days, the Basque Country underwent moments of political turmoil experiencing situations of relevant importance. One of them was the press conference given in Bilbao by the vast majority of parties and trade unions of the Southern Basque Country supporting the disarmament process. Choosing not to participate were the pro-Spain right party, PP (governing in Madrid) and its ally, the UPN party of Navarre. The Socialists had representation of its party from the Basque Autonomous Community, but not from its sister organization of Navarre. The display of support was very powerful.

The house in Luhuso where French police aborted an attempt at disarmament in December 2016. El Diario Vasco

Another discreet meeting of great importance took place between the three Presidents of the three governmental bodies in which the historical Basque Country is divided, including representation of the ICV. The President of the Autonomous Basque Community Iñigo Urkullu, the President of the Foral Community of Navarra, Uxue Barkos and the President of the Northern Basque Community, Jean-Rene Etxegarai welcomed both the involvement of the aforementioned Commission on disarmament and the way that Basque society was experiencing the moment. In fact, the two parliaments of the Southern Basque Country had already officially expressed this position. Everything seemed to indicate that this time was serious and that police interference would not be a factor, as had happened some months earlier in Luhuso. Discreet diplomatic efforts on several fronts, which some day may be revealed more fully, seemed to be effective. This is how it happened.

October 2011

Obviously, the disarming of an armed organization is of great importance, from all points of view. But in the case of ETA, it should be noted that this has happened based on a prior decision which, undoubtedly, had greater significance: the definitive cessation of its armed activity. This took place in October of 2011 in the context of what was called the International Peace Conference of Aiete (the name of the palace in San Sebastián where it was held).

On October 17th of that year, a broad representation of Basque society and a number of international figureheads, many of whom with extensive experience in peace processes all over the world, met at Aiete. In a five-point statement, among other items they urged ETA to abandon its armed activity and urged the Spanish and French Governments to engage in dialogue to discuss exclusively the consequences of the conflict. Three days later, ETA accepted the challenge and made the declaration of the permanent cessation of their armed activities, taking another step forward from the truce announced in September of 2010 and the permanent, general, and verifiable character added to it in January 2011. The Governments of Spain and France refused to respond to requests that were made to them at the Conference.

Undoubtedly, a series of circumstances made the new scenario possible. Included here is the reflection that took place in the pro-independence left-wing which had historically accepted the vanguard role of the armed organization within the movement. On the one hand, it was aware of the enormous rejection that ETA produced in Basque society and its obvious weakened state; on the other hand, its organizations were deemed illegal and not allowed to participate in elections or in governmental bodies.

Txetx Etxeberri gives the locations of the ETA caches. El Diario Vasco

There were compelling reasons (though not the only ones) that pushed the leaders of the pro-independence left-wing to boost a strategic shift, whose first important stage was the Aiete Peace Conference of 2011. Along this path a new party was legalized, which, in its statutes, had to pass through the painstaking filter that the Spanish courts demanded and formed an electoral coalition with other parties, which was undoubtedly successful in May and November of 2011. It was the reward for a part of Basque society that appreciated the new scenario. Paradoxically, the Spanish Government kept the leaders of the pro-independence left who had driven this impulse incarcerated, among them its maximum exponent, Arnaldo Otegi.

This time it seemed it would be definitive. For decades there had been other cease fires and also negotiating processes between ETA and the Spanish Government and even processes of dissolution and reintegration of one of the historical branches of the armed organization. Logically, there is not a single version on the rupture of those truces and the failure of the negotiations, but there is one undeniable fact: in October of 2011, ETA found itself in a situation of extreme weakness and with a complete lack of ability to uphold what had been a key objective for the organization, namely, political negotiation with the Spanish Government. What at one time perhaps may have been possible was no longer.

This largely explains the arrogant and contemptuous attitude of the Spanish Government of the right-wing Mariano Rajoy in relation to these new times (Would it have been different if the Socialists had remained in power in Madrid?) and also the fact that, from October 2011 to April 2017, ETA had made all of its decisions unilaterally. All this also explains that many people recognize that what is happening in the Basque Country is not really a peace process in a strict sense.

The Battle of How to Tell the Story

After the disarmament, there is still a long way to go. From the very moment ETA and the peace artisans announced this decision, voices began to speak up saying that this was not enough and that what was really important was for the armed organization to announce its dissolution. In fact, there are some voices who believe that ETA should not be dissolved and should be converted into a civil organization, yet others say that such dissolution should not happen until the problem of prisoners and exiles is resolved. But above those opinions is the overwhelming majority of Basque society who very clearly sees that the dissolution must arrive soon. Even ETA has announced a process of reflection in this regard. Anyway, it does not seem that this is the most urgent issue for Basques, who seem to be more focused on looking toward the future…and reflecting on the past.

The great Basque sculptor, Jorge Oteiza, used to say that progress should be achieved as oarsmen do: observing what is left behind. And right now a large part of the social, political and institutional agents of the Basque Country are focused on that, after decades of killings, kidnappings, threats, extortion, and torture. After decades of suffering that have left wounds difficult to heal.

The French police inspect one of the cache locations in Senpere (Province of Lapurdi). EFE/Guillaume Horcajuelo

Words like reconciliation, justice, reparation, victims and memory are on everyone’s lips. Major social and institutional initiatives are underway to address such issues, among which perhaps the most ambitious and elaborate is the Plan for Coexistence and Human Rights of the Basque Government (2017-2020), which takes over from the previous Peace and Coexistence Plan. It is a goal shared by the vast majority of Basques to promote a culture of coexistence, to make a critical reading of what has happened during the last decades and to work so that this scenario of suffering is not repeated. Although a lot remains to be done, it is obvious that much progress has been made and that there are common denominators that the overwhelming majority accepts. But it is not easy, because to a large extent, deep down lies what some people call the battle of how to tell the story.

Despite the efforts of some, it seems clear that it is very difficult to impose on Basque society a single account of what has happened during ETA’s years of existence. Among other things, because the ideology, strategy, and actions of the ETA organization (of all its branches) over time have been enormously disparate. While it is true that ETA has reached 2017 with the rejection of the vast majority of Basque society, throughout history this has not always been the case. Among Basques there were those who supported ETA until it began killing; some supported them until the dictator Franco died in 1975 and saw that it was time to quit; some until the 1977 amnesty agreement; and some until they began indiscriminate attacks or killing journalists… There are also Basques, many Basques, who never supported ETA.

This is one of the reasons it seems like mission impossible to agree on a single way to tell the story. For example, does the death of a sadistic torturer such as Melitón Manzanas or that of the genocidal Prime Minister Carrero Blanco in the worst years of the dictatorship deserve the same judgment as that of a councilor of a Basque town elected by its citizens in full democracy? For many Basques the phrase “killing was always wrong” answers that question. For many others, this statement deserves at least some clarification. The issue is so complex that we can find ex-ETA members of different times in all Basque political parties today, from right-wing pro-Spain to left-wing pro-independence.

The purpose is, therefore, to make advances toward coexistence realizing common interpretations on the suffering that the violence causes and its dire consequences; supporting the victims; advocating truth, justice and healing; and finally, working so that it never happens again. But renouncing the imposition of a single version of the story, which, in addition to being impossible, can be counterproductive.

President Urkullu giving his point of view on the disarmament along with Ram Mannikalingam. El Diario Vasco

And let’s not forget that during these decades there has also been another kind of terrorism, terrorism that took place on many occasions in the sewers of the Spanish government, which also brought about many victims and suffering, as well as police abuses that have gone unpunished. Unfortunately, there are some people who do not want to recognize such a reality and they prefer to hide it. In this sense, it is particularly significant that the Spanish Government has appealed a law on victims of police abuses approved by the Basque Parliament in December 2016, as it did earlier with another similar law of the Navarre Parliament in 2015. Madrid has justified such action with legal arguments, but it is pretty clear for many that deep down there is a political motivation.

The Future of ETA Prisoners

It is evident that in this new scenario which first began in October 2011 with the cessation of ETA’s activity, and subsequently in April 2017 with its disarmament, major movements are taking place in many areas. But no one can deny that one of the largest controversies being generated is about the situation of prisoners and exiles that the armed activity produced for so many decades.

Although their number has declined over the past years, there are still nearly 400 activists imprisoned in Spanish prisons (the vast majority) as well as in French prisons, but there are also some prisoners in other countries. The accounting of the exiles, most of which are in Latin American countries, is more difficult to track, since their personal situations are quite different.

Both ETA and the pro-independence left-wing party historically related to it are aware that what was their aspiration, namely, the achievement of amnesty, is now unattainable. Logically, they maintain this claim as their banner, but all steps that they are taking during recent years are aimed at finding another kind of output where amnesty is not a condition.

Thousands of people celebrate the disarmament in Bayonne. El Diario Vasco

On the one hand, they are demanding freedom of prisoners suffering from serious illnesses and the end of the policy for dispersal of inmates at multiple prisons, moving them to prisons located in the Basque Country or closer to it, so as to avoid an added punishment to family members who are forced to make lengthy trips for visits. These are some of the requests also supported by the vast majority of Basque society, as demonstrated in multiple social mobilizations and initiatives by Basque institutions. Organizations like Sare (network in Basque) and Foro Soziala (Social Forum to Promote the Peace Process) are constantly promoting initiatives to achieve these objectives. Also, the so-called peace artisans have announced a demonstration in Paris this December calling for the end of the measures of exception that apply to prisoners.

On the other hand, both ETA and its official group of prisoners (EPPK in Basque) have been taking steps over the past years and gradually accepting individual solutions that until now were flatly rejected by them. But the principle of reality has prevailed and, aware of the impossibility of amnesty or a global solution, they have finally accepted matters such as change of prisoner status, permits, working in prison and another series of individual benefits, always without surpassing the limit of repentance and informing.

The change is impressive, because in the past, former militants of the organization that accepted individual benefits were denigrated, expelled and even killed. No one knows more about this than prisoners and ex-prisoners of the so-called Via Nanclares (named after the prison where they were incarcerated) who are participating in a reintegration process in which they meet with their own victims or with victims caused by the organization they were once a part of.

But outside the official EPPK group there is a small number of imprisoned dissidents who have branched away from this strategic shift, which they consider a surrendering. Outside the prisons they count on the support of the Movement for Amnesty and Anti-repression (known as ATA), which organizes demonstrations frequently. It is too early to quantify the importance of this dissent, but it is clear that it is a group significantly smaller than EPPK inside the prisons and also smaller than the official pro-independence left-wing party outside the prisons.

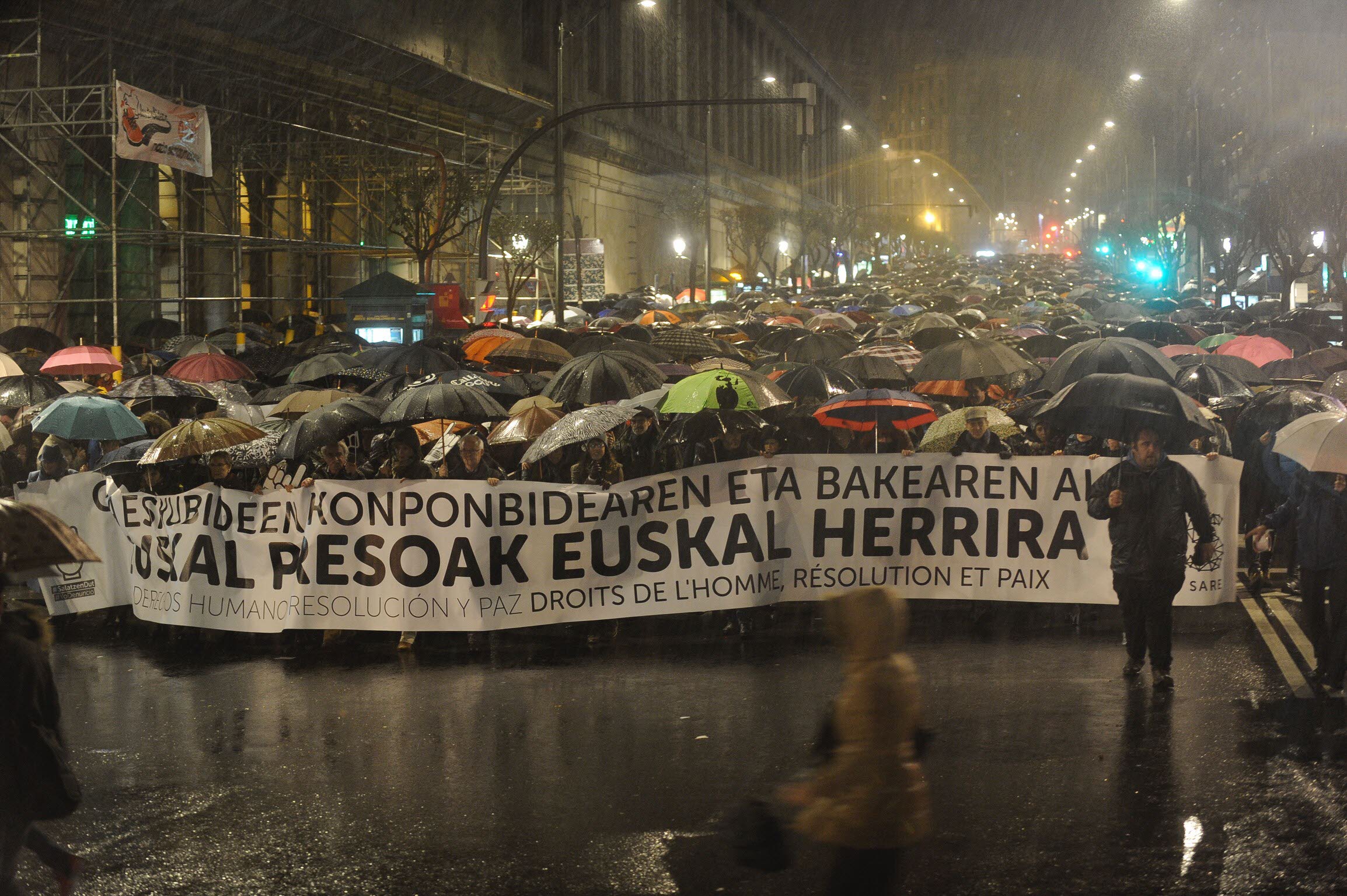

January 2017. Demonstration in Bilbao for prisoners’ rights. El Diario Vasco

In this context, but in a more discreet manner, efforts are also underway in the political and governmental areas. It is known that in regularly held meetings by the Basque Government and the Spanish Government, prison policy is a topic that is always on the table. This topic is also ever present in talks between political parties that support both Governments: PNV (Basque National Party) in the Basque Autonomous Community, in coalition with PSE (Socialist Party) and PP in Spain. The Basque Country has pushed with insistence for a change of attitude from Madrid which the more optimistic believe will come. This is also expected of the new French Government of Emmanuel Macron, with about 80 ETA prisoners being held within French territory.

In short, while this is a new and exciting time for the Basque Country it is also extremely complex, with many wounds to heal, with a lot of accumulated suffering, many ignored victims, and with much work to be done looking toward the future. One of the most notable issues is also the weariness and fatigue of the greater part of a society that sees the issue as already exhausted. Certainly this is a society that seeks healing for the victims, a society seeking justice, and a society that wants a solution for the prisoner issue, but a society that mainly wants to move on and leave it to others to solve these problems. It is an issue that should be of great concern to the Basque political world.

Be the first to comment on "The Basque Country after the Disarming of ETA"