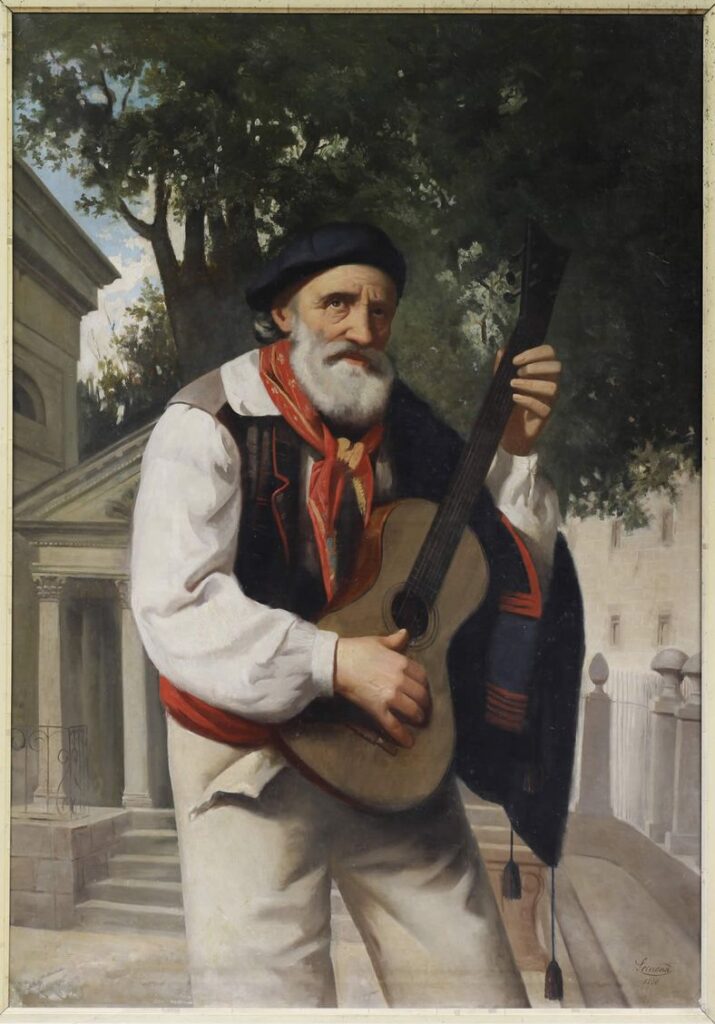

This past August 12th, an important group of Basque musicians made public in Pamplona a statement proposing that the song Gernikako Arbola (the tree of Gernika) be recognized as the anthem of the Basque Country. The date chosen for the event was not by chance, it was the 200th anniversary of the birth of Jose Maria Iparragirre, the composer of this song, a prominent figure in the history of the Basques.

Since that presentation, the initiative has had significant additions: in academia, a large group of historians have joined the idea, through another statement, of recovering and revaluing (those are the verbs they use) the Gernikako Arbola. In the political sphere, the support of a large group of historical militants and leaders of the pro-independence left, supporting the petition has also been significant. The song has become so relevant that a book has already been published by editor and writer Jose Mari Esparza, one of the leading advocates of the cause. Other voices, however, have disagreed with the proposal, though not all for the same reasons.

Some Weighty Arguments

The promoters of the initiative argue that there are profound reasons that make it necessary to give the Gernikako Arbola idea a push. They claim that since Iparragirre first sang it in Madrid in 1853, it expanded rapidly and became a universal hymn sung by citizens of all the Basque territories and also throughout the diaspora, regardless of their political stance and feelings of identity. They recall crucial moments in our history in which this composition played an important role.

They also remember that despite the current political-administrative division of the Basque Country, Basques from all territories have managed to maintain a language, the name Euskal Herria and a series of cultural, sporting and social manifestations that self-identify the Basques as one people. In that context, in their opinion, the song Gernikako Arbola best represents this spirit.

Certainly, the Autonomous Community of Navarre has already had its official anthem since 1986, the Nafarroako Gorteen Ereserkia (Anthem of the Courts of Navarre) inspired by a Baroque melody played in the cathedral of Pamplona upon the arrival of the ancient Courts. As for the Basque Autonomous Community, it has its Gora ta Gora (Up with…), an anthem approved in 1983 by the Basque Parliament, but which was also designated as an official anthem in the first Basque Government of 1936. It is mainly the defenders of this hymn who argue with the proponents of Gernikako Arbola over the viability of their proposal.

Arana and Zabala’s Anthem

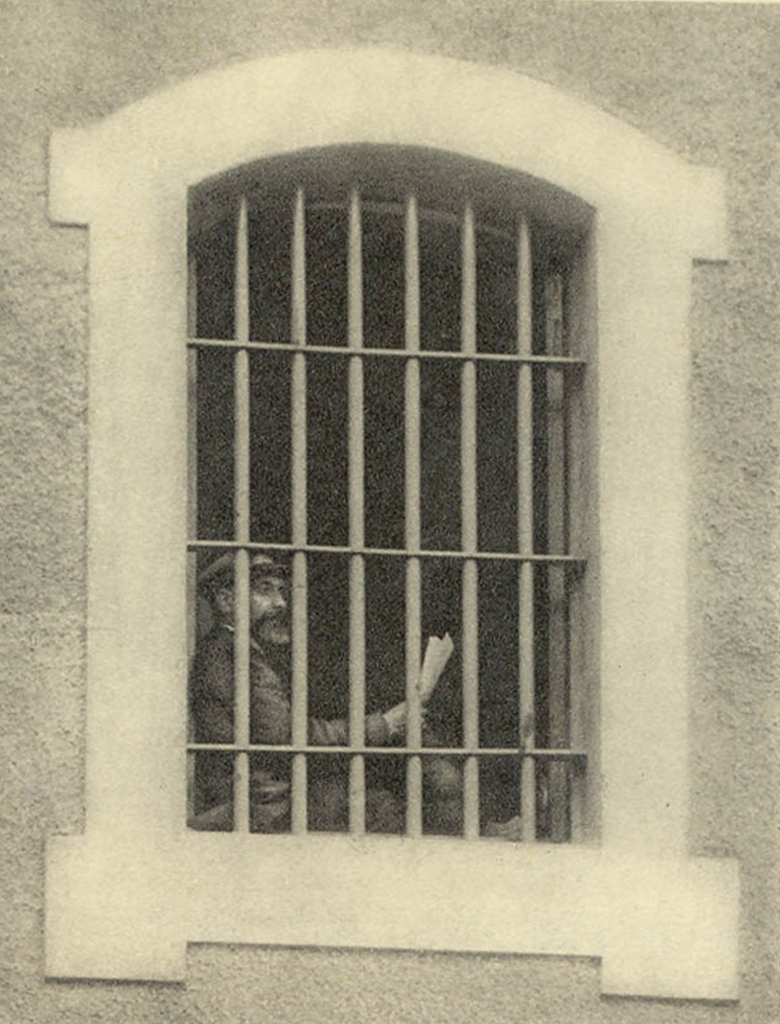

Gora ta Gora was composed by Cleto Zabala in 1903, based in part on the melody of a Basque dance. The lyrics were written by Sabino Arana a few months before he passed away. The father of Basque nationalism was then imprisoned but led fervent political activity. Initially, it was composed as an anthem of the PNV (Basque Nationalist Party), the party which he founded, but, as we have pointed out, it was adopted by the Basque Government of Jose Antonio Agirre in 1936 and, once Franco was deceased, was also adopted by the Basque Parliament in 1983, and has been official since. Lehendakari (former President) Carlos Garaikoetxea explains in his autobiography that he was aware that the decision to retrieve the anthem would be a controversial decision which would not reach consensus. And that’s what happened.

The opposers of Arana and Zabala’s anthem feel that it is a composition linked excessively to the PNV and is perceived as such by an important part of the Basques. In addition, they believe that the fact that it is an official anthem of one of the current Basque administrative divisions prevents it from being adopted as its own by the Basques of the other territories. On the flip side, the defenders of this anthem answer that it is in a similar situation as the Ikurriña (the Basque flag), because although initially it was also the political party’s flag, and was officially approved only in the Basque Autonomous Community, the rest of the Basques also feel like it belongs to them. The advocates of Gora ta Gora add that the Basque Government of 1936, which unanimously approved this anthem, was not only made up of nationalists, but also had communists, socialists and those in favor of the republic as members.

However, regardless of its similar origin and its current legal status, the truth is that the low legitimacy and social recognition that this anthem has had is not comparable to the immense acceptance of the Ikurriña throughout the Basque territories. In short, in the opinion of some of the citizens, Gora ta Gora is the anthem of the whole Basque Country. Others accept it as an anthem of the Community that form the provinces of Araba, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa but not for the complete Basque territories. Finally, for another sector of society, it should not even be admitted as such. So, it’s understandable that there are initiatives in search of a more accepted hymn such as Gernikako Arbola.

The beautiful composition of Iparragirre hardly arouses discord among the Basques. It’s true when the promoters of the initiative argue that it is a more inclusive song. However, there is a fundamental obstacle that prevents this initiative from meeting its objective of becoming the anthem of the Basque Country. For a part of the Navarrese citizens (probably the majority) this is a debate that is alien to them, since some of them do not feel Basque at all. And as far as the Northern Basque Country is concerned, they obviously consider themselves Basque, with Ikurriñas waving from their official buildings even if they have no official recognition. Yet moving this initiative forward in terms of recognition of a hymn that reaches beyond nationalist sectors seems difficult because, although they are growing, they are still a minority. Therefore, the August 12th statement is taking a well-spent journey but is limited by the socio-political reality. Given the impossibility of institutional recognition as an official anthem, it is a question of promoting its knowledge and use in other social circles. But in order to do this, another debate has also been opened that is not a small one: that of its lyrics.

The Issue of Lyrics

Being from the mid-19th century, it seems logical that in the original composition of Gernikako Arbola its terminology is not in line with current secularism. Thus, people who support the initiative to promote the idea of an anthem have suggested that changes be made to its lyrics, something similar, by the way, to what the Australian Government has just done to recognize its Aboriginal population. For many other people, however, the lyrics are not a significant problem.

The truth is that the lyrics are an issue that matters in the Basque Country. The song Gora eta Gora was approved in 1983 without any lyrics at the request of the CDS, a Spanish centrist party whose votes were necessary, but also because the PNV acknowledged that the 1903 lyrics could not appear as an official anthem. In fact, the initial name of the composition, Euzko Abendaren Ereserkia (anthem of the Basque race) has also been banished because of obvious issues and gradually replaced by the first words of its original text. Another solemn Basque composition such as the Agur Jaunak (Greetings Gentlemen) is also up for revision in order to fulfil gender equality and introduce women into its stanzas. By the way, the Agur Jaunak has always been on the table every time there has been debate about the anthem of the Basques.

As you can see, Basques are reflecting and debating over their anthem and their hymns, thanks to this opportune initiative that started on the centenary of the birth of the great Jose Maria Iparragirre. Whatever the end result of this movement, the truth is that it is having the beneficial effect of seeing many Basques taking an interest in the history of their people in relation to the topic, as well as the biographies of the composers being discussed. The anthem is a praise to the legendary oak of Gernika, the symbol of Basques for centuries.

Ona da Iñaki, interesgarria.