by Harri X. Fernandez Iturralde

Gregorio Muro, Joseba Larratxe and Dani Fano, three authors from different generations of Basque comics talk about this emerging sector.

The health of a culture and a language is measured by the number of its speakers or consumers, but also, of course, by the supply of materials developed in that language. It can be said that literature and music in Basque are two disciplines that have been established for years from the point of view of creation. Almost two decades ago, cinematography caught up. Not surprisingly, in recent years the Basque Country has experienced what is known as the blossoming of Basque cinema, which is beginning to show signs of being a full-blown industry. Now, it seems that a new art form is resurfacing, thanks to the efforts of individuals and also public institutions: comics. If we look at the data at Komikipedia (komikipedia.eus), a collective and open project focused on collecting information related to the production of comic strips in Basque, 2022 was the record year with the publication of 52 printed albums, six in digital, and seven reissues. In 2023 so far, 22 titles have already been published.

Fifty works a year may not seem like much, especially when compared to the number of titles published in Spain in 2022: 4,563 in Spanish, of which only 630 were works developed in Spanish by Spanish authors. The remaining nearly 4,000 were translations of the world’s main comic traditions, namely the American comic book, the French-Belgian album or Japanese “manga”, not to mention the generic concept of the graphic novel, which even today continues to generate heated debates about the accuracy of its definition. In the case of Basque, although the production of Basque authors has grown, for now imported comics, especially from the neighboring markets of France and Spain, account for the majority of those published.

In this context where the borders are grey, it is also true that there are Basque authors who work from the Basque Country for the great American comic book publishers. This is the case of Angel Unzueta, who, from his studio in Zarautz, has drawn important covers such as Ironman or Captain America for Marvel Comics, several Star Wars series and, currently, illustrates the series Star Trek: Defiant for IDW Publishing. Another case is that of the Álvaro Martínez Bueno from Cantabria, Basque by adoption, who has been working in Donostia for years and who has been in charge of such important characters as Batman for the DC Comics publishing house. Last year he won the Eisner Award, the comic book Oscar, and the most prestigious of these awards, for his twelve-issue series The Nice House on the Lake. Others, such as Iñaki Holgado of Errenteria, produce for the French-Belgian market.

Regardless of authors who work abroad as a personal option, it is interesting to analyze those who do so in the Basque Country and for the Basque Country. Thus, the increase in the supply of the ninth art in Basque is significant compared to the beginning of this century. Continuing with the data of Komikipedia, between 2000 and 2010, the number of comics published in Basque per year did not exceed ten titles. The trend began to change in 2010 and was accentuated in the middle of the last decade, when the Basque Government approved four different types of grants with annual aid for the creation and development of comics in Basque. Three generations of Basque authors, who have witnessed the evolution of the graphic novel in the Basque Country, offer a multifaceted perspective in this article of a sector that is beginning its path toward professionalization.

Gregorio Muro (Hernani, 1954), known artistically as Harriet, is one of the figures who best knows the sector. He began in 1978 as a screenwriter for the magazine Ipurbeltz, of the publisher Erein. A publication that, in full openness of post-Francoism and accompanying the expansion of education in Basque, opted for a product aimed at children and young people. Faced with the impossibility of carving out a professional career in the Basque Country, Harriet jumped into the European market and began publishing with important French publishers such as Glenat Dargaud and Humanoides Associes. The result of this collaboration would emerge in French as one of his most notable successes, Justin Hiriart (1988), a story focused on Basque sailors who traveled to Newfoundland to hunt whales. Later, in the 90s, he immersed himself in the audiovisual world, scripting several animated and live-action films. But it was in 2015 when he embarked on a new professional adventure. He created in the province of Gipuzkoa the Harriet publishing house, exclusively dedicated to comics, with a three-part objective: to give an opportunity for Basque authors who wish to develop work, to import comics that interest him as a publisher, and to recover the rights of his own works to offer them to the Basque-speaking public.

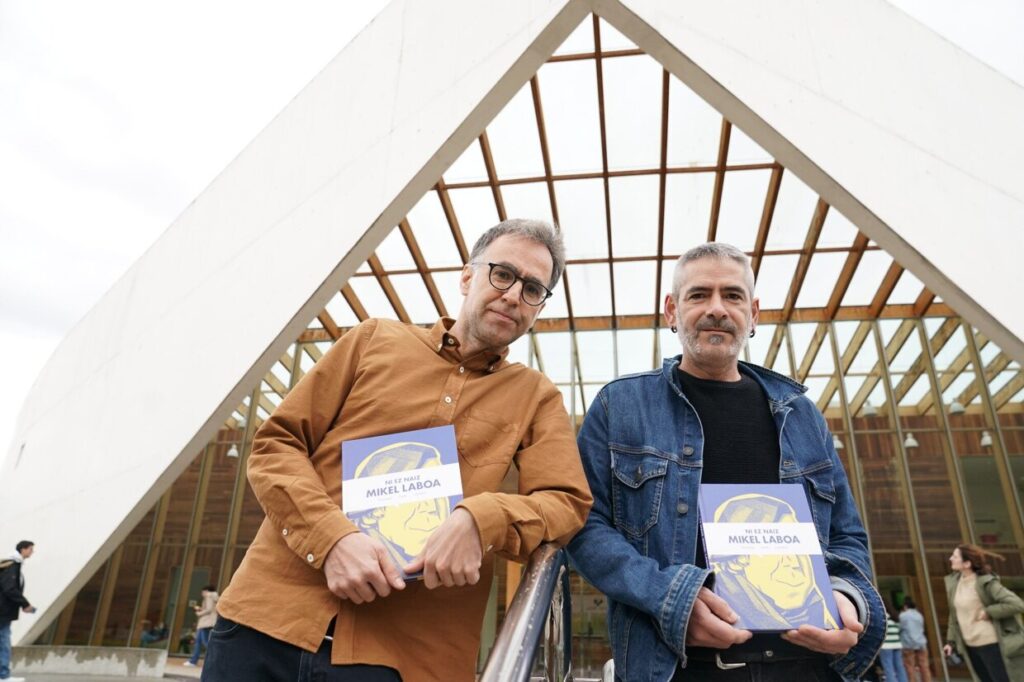

Gregorio Muro frames the healthy state of this art in the Basque Country in line with a general trend. The comic book has ceased to be a niche product for very specific audiences. Its stigma has been removed and it has become democratized as a cultural product. Along with the wave behind this format, local, powerful, young talent are emerging with very different styles. This is the case of the illustrator Joseba Larratxe (Irun, 1985), known artistically as Josevisky, who under Harriet’s wing published one of the most celebrated Basque comics of recent years, Joana Maiz (2019), with a script by Yurre Ugarte, and who in addition to the Basque market, last year jumped into French. From the hand of Larretxe another more than remarkable work has also emerged, Ni ez naiz Mikel Laboa (2022), written by two artists, Harkaitz Cano and Unai Iturriaga, in which the artistic trio approaches the figure of the singer-songwriter from a complex perspective, closer to reverie than a rigorous biography.

“For there to be awareness, there have to be comic books on the market,” says Muro. In this sense, in addition to public funding and the impulse of the creators themselves, there is also another factor to take into account: the commitment of publishers. In addition to Harriet, Farmazia Beltza and Astiberri, labels focused exclusively on the ninth art, large general publishers such as Elkar, Txalaparta and Erein have also published comic books in Basque. In fact, Erein has just published for the first time in Basque in an integral part the first three stories of Irati, by Juan Luis Landa and Joxean Muñoz, an original work upon which Paul Urkijo’s successful film is based (another milestone in Basque cinema that is now available on Amazon Prime).

Can You Make a Living from Comic Books in Basque?

There is another determining factor in defining whether a sector is fully developed or not: the economic conditions of the creators. In this sense, both Muro and Larratxe highlight the importance of the approval of a series of aid for creation by the Basque Government. In fact, Ni ez naiz Mikel Laboa could be carried out in optimal conditions for its authors due to having received two public grants, the aforementioned one from the Basque Government and the allocation of the Mikel Laboa Chair that the University of the Basque Country launches every year to dive into the legacy of the author of the famous theme Txoria txori. Larratxe makes it clear, in his case living exclusively from comics is very difficult or practically impossible, something that is not exclusive to the sector in the Basque Country, but is something generalized. “I live from drawing, not from comics.” (Larratxe also illustrates books, posters, logos…) Muro adds to this idea by expressing it in a graphic way: making an album can take a lot of months and the profits per copy sold can only be profitable if the windows in foreign markets are included.

For the illustrator of Joana Maiz, one of the ways to live professionally and exclusively from comics in the Basque Country is through the publication of daily press strips, as do authors such as Patxi Ugarte from Navarre, popularly known as Zaldieroa and who publishes in newspapers such as Berria or in the weekly Ortzadar linked to Grupo Noticias. The other option, Larratxe continues, would be to go to other markets, as Angel Unzueta has done. The creator from Irun, however, prefers to publish in the Basque Country and for the Basque Country, “It’s a personal choice, but when I create, I am contributing to my community, the Basque community, something that goes beyond a purely economic issue,” he says. He goes into more depth. For him, the perfect formula would be to be able to create in the Basque Country, with a spirit that reflects this tradition, and then to be able to export his works to other markets so that the creative potential of the country and its vision are also recognized. “If a Basque creative couple, from the Basque Country, creates a work with Basque themes in the Basque language and then it is exported, that’s when we are contributing something,” says Larratxe.

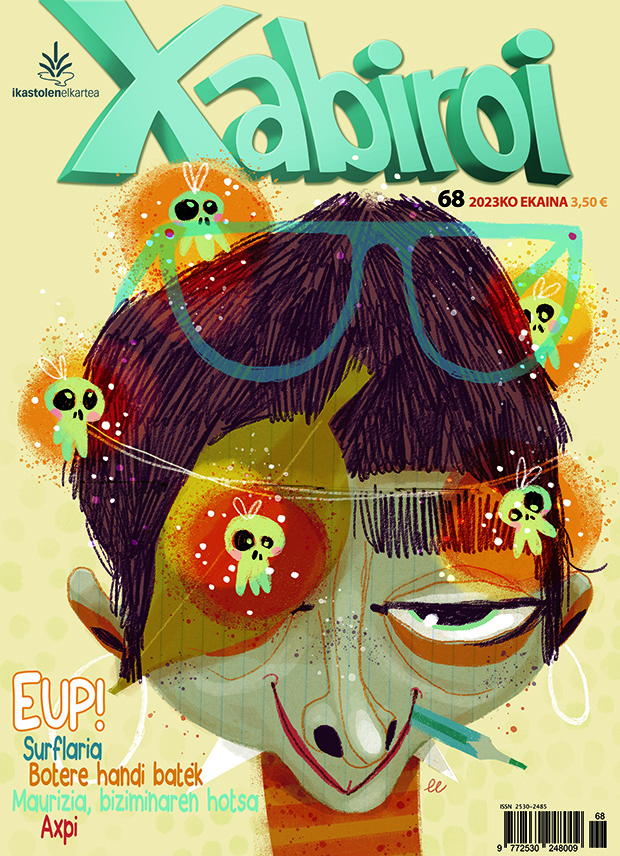

The Magazines: Ipurbeltz, Habeko Mik and Xabiroi

Magazines such as Ipurbeltz (1977-2008) served as a catalyst, explains Muro, for artists with certain creative impulses as an outlet for their art. Those were times when the Basque sector was non-existent, Spanish was still very weak and still fed from French formats and jumping the border to publish in France was something very difficult for new artists. Although Ipurbeltz was aimed at children, between 1982 and 1991, HABE, the Institute for Adult Literacy and Revitalization of the Basque Language under the Basque Government, published the magazine Habeko Mik, thinking of an adult audience. “It was a great moment that was slowly diluted,” says Muro, who adds that both magazines generated a creative fertile ground of high quality, a moment in history that seems to resonate with the current situation.

At present, in fact, neither of these two publications is still being published. On the other hand, at the beginning of this century a new magazine was created, Xabiroi, directed by another author, the illustrator Dani Fano (Donostia, 1968), who in 2018 published his extensive work Migel Marmolen hamaika eta bat jaiotzak. “If the Basque comic sector exists, if we could say that something like this exists today, it has been thanks to Xabiroi and Dani Fano,” says Larratxe, an author who, like many other “professional authors” of his generation, has seen his cartoons published in this magazine. This, of course, has allowed the collective to exchange experiences and create strength in numbers.

“The sector is better off than years ago, but there is still much to be done,” says Fano, who adds that much more important than the number of comics in Basque that are published are the working conditions in which these works have been developed. And even nowadays, as it’s been mentioned previously, there is a lot of precariousness. In this regard, the aid that has been emerging has been key so that authors can take the necessary time to develop quality works, which allows at least four works a year to be published in adequate conditions. The same goes for Xabiroi, adds its director. With four issues a year, it allows authors to publish in good conditions and in a timely way. For a sector to develop, says the artist from Donostia, it is necessary that there are references that are maintained over time. That is another of Xabiroi’s roles, which allows to create a network of artists. “When we started with Xabiroi in 2005, the world of comics in the Basque Country was a desert. There were already authors, they already existed. What was missing was to give it shape and what Xabiroi did was just that, to shape it, not only publishing comics, but also building relationships between the authors,” says Fano.

From the Spanish “Tebeo” to Japanese “Manga”, in Basque

We have cited 1977 as the year Ipurbeltz was founded and as the start of a chain of circumstances that brought the Basque comic book sector to its current state. However, it is convenient to focus on a precedent to all this and, at the same time, on a new line of work that seeks to attract new reading audiences. At the beginning of the 60s, with the impulse of Joseph Camio, honorary member of the Basque language academy, the Catholic magazine Zeruko Argia, which was published in the French Basque Country to circumvent Franco’s censorship, began to publish the children’s supplement Pan-Pin, focused on the ninth art. It was not a publication that promoted its own creation, but translated into Basque comics of many popular characters of the Spanish “tebeo” (comic strip) of the time. The objective was clear: in the face of a non-existent sector, to offer cultural material for the literacy of the youth. More than half a century later, Gregorio Muro launched a new line of work in his publishing house with a similar spirit. Europe is currently experiencing a boom related to Japanese “manga”, which has a lot to do with the proliferation of animated series that have come down to us thanks to streaming platforms. In this context, Harriet has founded the Kabe label with which it seeks to publish ten “manga” titles a year directly in Basque (the first title published, Cube Arts, was a success in terms of sales), something new considering that the comics that are imported come from neighboring markets, as already mentioned. For example, in the Basque Country reading Superman, Batman, Spiderman or Iron Man speaking in Basque has never been possible. But that day will soon come.

Be the first to comment on "Comics in Basque Making Their Way"