Being imprisoned has to be the ugliest way to “be” ever. So, what could be better than being set free? What could be more beautiful than escaping from this condition?

Like Papillon, or the protagonists of the escape from Alcatraz, one who decides to escape from prison, dreaming of freedom, will use all the courage and imagination available. With the combination of these two elements, many escapes are almost works of art. When we learn more about them, almost inadvertently, an unprejudiced sympathy emerges in us for the cunning escapee; and not only a feeling of finding ourselves before a real situation that would seem to be an adventure story, but because of the fact that the escapee has outsmarted judges and prison guards, those who are responsible for depriving freedom from fellow man; and above all, because it has given us living, empirical proof that even the most impossible can be achieved. A tangible claim to continue dreaming in a utopia.

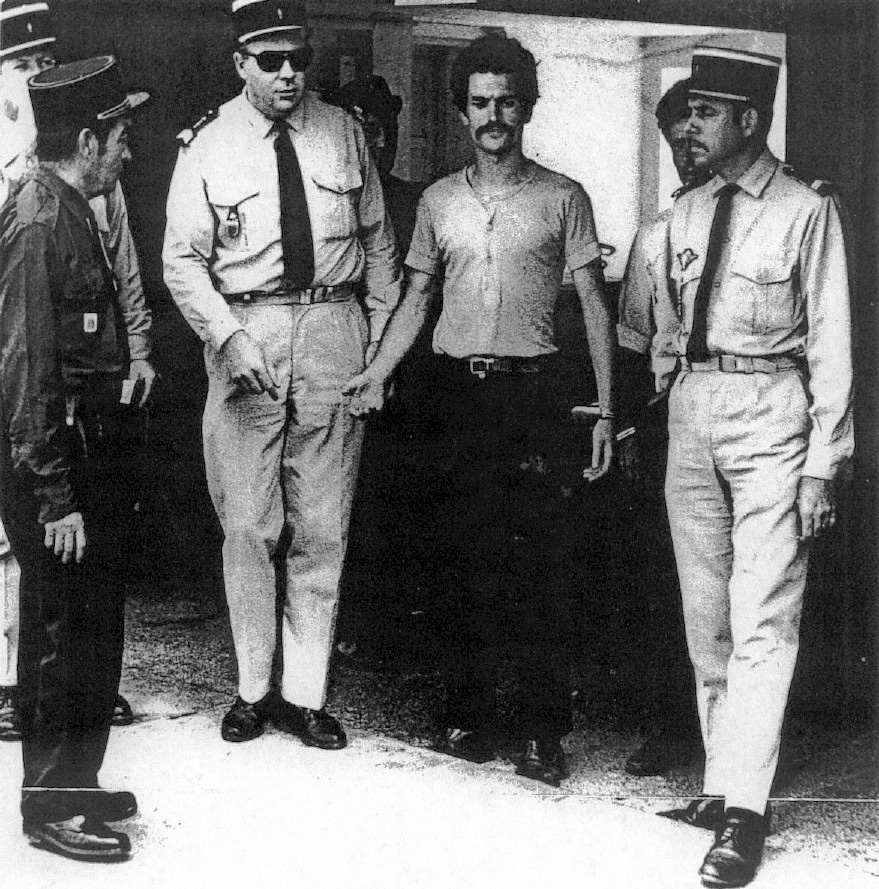

The Catalan anarchist Oriel Solé arrested in 1971. In 1976 he fled Segovia (Spain) together with Basque prisoners, but police killed him before crossing the border. Photo: Elkar

In the book Tunelak, izarak, mozorroak eta bafleak (Tunnels, sheets, costumes and loudspeakers), I tell the story of 10 escapes that occurred in the last 50 years, linked to the so-called “Basque conflict”. Some with happy endings, and others that went wrong. Some performed alone, and others in groups. Some pretty well known, and others less so. But all of them full of courage, ingenuity and imagination.

Cover of the Basque press after the historic Martutene Prison Escape in 1985 (the Basque Country.) Photo: Elkar

Among the best known is the escape of Segovia of 1976 which was made into a film about the attempted escape of some twenty inmates, of which only 3 managed to cross the border. Although most were Basques (of the ETA political-military branch, in particular) there were also three Catalonian escapees, and it is from the testimony of one of them that this story is told in a movie which we have seen so many times aired on ETB (Basque Television).

The Martutene escape of 1985 is no less mythical. The singer Imanol gave a concert in prison, and at the end, Basque prisoners Joseba Sarrionandia and Iñaki Pikabea, managed to escape, hidden inside the speakers (obviously previously empty). The fact that Sarrionandia is a writer, the song Sarri Sarri by the rock group Kortatu referring to this escape, and the fact that since then he went missing, have made this episode commonplace in our recent history among generations and an indispensable part of the Basque collective imaginary. So, the book addresses the situation from the testimony of the “other” escapee, from Iñaki Pikabea’s point of view, who tells in great detail about the imaginative getaway.

Other prison breaks (or attempts) recounted in the book are the escape of Pau of 1986, or that of the two brothers of 2002. The first of these, the escape of Pau, is a story that would be well worth another movie. It is about the liberation of the members of Iparretarrak Gabi Mouesca and Maddi Hegi by another cell of the armed organization of Iparralde (the Northern Basque Country). After preparation that lasted months, the cell managed to use French police costumes, and after kidnapping the director of the prison and “convincing” him to work with them on the plan, the false French police entered the prison with the director and gave the order for the transfer of Mouesca and Hegi, and took them right out the front door without a single shot fired.

Maddi Hegi being arrested in 1985. A year later she escaped from the prison in Pau (France.) Photo: Daniel Vélez

As for the “switch” of the Berasategi brothers in the Paris prison of La Santé, this is a story that would merit a Nobel Prize for imagination. Joseantonio Berasategi, worried about his brother Ismael, prisoner in Paris, decided to impersonate him, switching places during a vis-à-vis. After several months of planning to the millimeter how to carry out the switch, and without telling a soul, one day he went to visit his brother, and when the visit ended, the prisoner walked free, and the free brother went back to the prison cell. No one realized until, two or three days later, Joseantonio himself told the prison guards that he was not who they believed he was.

In this brief article there is not enough space to talk about all the prison escapes that appear in the book. It doesn’t matter, and it would be a disservice to try to do so anyway. Whoever wants to delve into the subject and can read in Basque, has the book available in any Basque library or on the Internet. There you can find, as well as the chronicle of 10 escapes of the past 50 years, a chronology of incurred attempts, a collection of photos, maps and newspaper clippings, and an epilogue written by an esteemed collaborator: Joseba Sarrionandia.

Be the first to comment on "Ten Goodbyes"