Last 26 November, Gernikako Arbola’s 170th anniversary celebration was held in the town of Urretxu, Basque Country. The Basque anthem is the most successful song delivered by the singer songwriter Jose Mari Iparragirre. Before its commemoration, several articles were published in the Basque-language newspaper Berria, including a poll on Twitter, or X, on the preferred anthem of the Basques. That might as well suggest an idea of the present-day perception on the topic, but it may also come across as a matter of fashion and mood, associated with personal, fleeting fancy, a tabula rasa. It occurs to me that the question should rather be something along these lines: “Do you want the Gernikako Arbola to remain the national anthem of the Basques?

The Gernikako Arbola is a lieu de memoire or milestone in our collective memory

We have come a long way. For a start, the Gernikako Arbola is a lieu de memoire or milestone in our collective memory, a concept addressed by Antoni Furió, among others, at the conference held in Oñati by the cultural organization Nabarralde in 2018. A national anthem is supported by an epic; it has been present in the important historical events of a people, even in war and its most critical moments. It requires a great deal of consensus, and it sinks its roots in all the territories concerned, in this case the Basque Country, but historically also in the important Basque Diaspora.

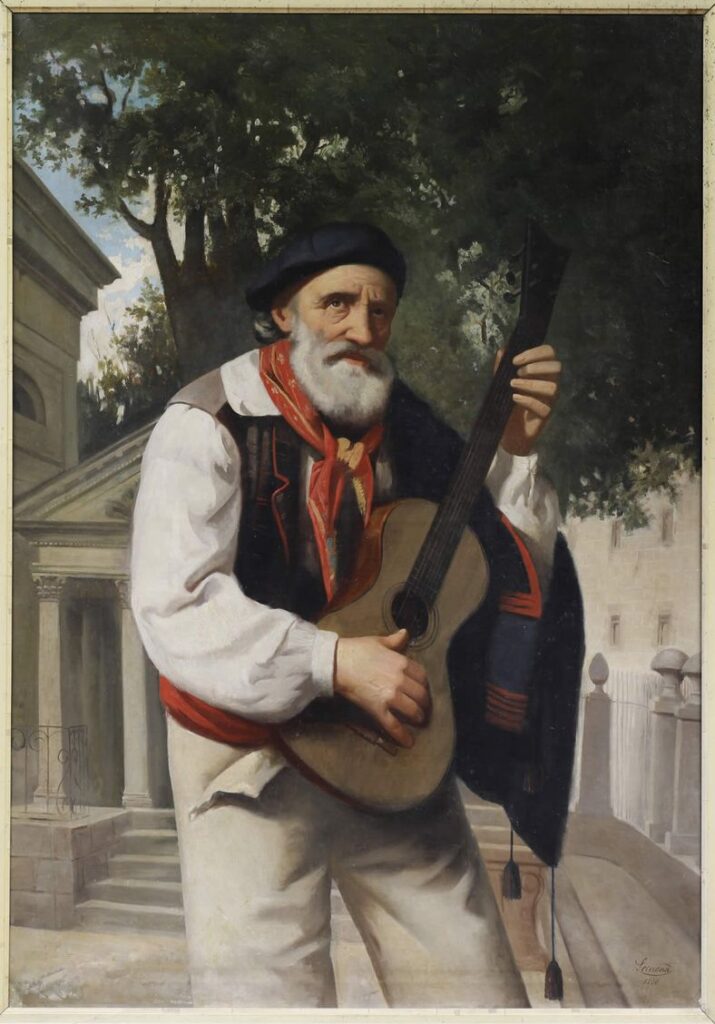

Iparragirre’s tunes disturbed Spanish authorities and officials for their power to agitate the population, when the continuation of Basque laws and institutions was at stake. This is how Iparragirre met exile in 1853 and came up with the Gernika Arbola in Madrid. The song took hold deeply among the Carlist combatants during the Second Carlist War (Third in the Spanish context), but also among the Liberals and later among virtually all political sectors. Sabin Arana preferred the Euskal Abendaren ereserkia, present-day anthem of the Basque Autonomous Community.

The Gamazada revolt with its main focus in Navarre (1893-1894) spread the popularity of Iparragirre’s anthem, singularly its first stanza, especially after the massacre perpetrated against protesters in Donostia during the Gamazada, an uprising for the freedoms of the Basques (as reported back then in the international press), as the crowd sang the popular Gernikako Arbola.

In the heat of the lore jokoak or Basque festivals in the French or Northern Basque Country, Iparragirre’s anthem became a solemn moment among the people, a handful of them scholars and authorities, most of the times just regular people. The Basques in the Diaspora and the Basques in general made it a symbol for cohesion, and the Basque soldiers forced into the “Great War” of 1914-1918 sang it in the trenches. In 1899 it became the first recorded Basque song, and the Germans recorded it from the Basque prisoners in German Prussia. By then, it was the Basque national anthem, die baskische Nationalhymn,l’hymne national des Basques, in Spanish himno del pueblo vasco, cited in plays, press and encyclopedias all over the world. Gernika’s bombing in 1937 increased the renown of the Tree of Gernika and its international symbolism.

However, by the 1960s, the more martial Eusko Gudariak was gaining momentum, to the detriment of Iparragirre’s song. The Spanish political transition following the dictator’s death in 1975 did the rest to play down the significance of the Basque national anthem: polarization and partisanship on the one hand, and generation gap on the other. I lived both myself first hand. The track Gernika koka kola was released in 1986 by the rock band Baldin Bada on an album as brilliant as it was irreverent. So was the song, breaking the rules as ideas came to mind. Speed and vitality, breach of sacred icons… a walk on the wild side.

In recent decades, generational transmission breakdown, denationalization and individualization have left their mark. The Spanish or French education curriculum probably does not explain anything about the Gamazada or the Gernika Arbola, and that is one of the keys. In addition, a song like Mikel Laboa’s Txoriak txori that appeals to the individual (“a bird”, “I”), however beautiful, inspiring and easy to sing (like the rhythmic Gernika Arbola), can hardly be a national anthem. It is always fair, of course, to sing and admire it, also the popular Ikusi mendizaleak, or Agur jaunak, even to reject any hymns whatsoever. But over the time, space and collectively, the Basques, eman eta zabal, give and expand.

Editor’s note: In February of 2001, Basque Tribune published another article about the Gernikako Arbola.

Be the first to comment on "170 Years of the Gernikako Arbola"