One kilometer from the center of Hernani (Gipuzkoa), the new dish-shaped building sits leaning toward the ground while another, of rectangular shape and built 43 years ago, gazes at it from not far away. The first one, with its groundbreaking aesthetics, belongs to the elevator company Orona (the first building in a business park that will house white coat industries as well as a new campus of the University of Mondragón). The Galarreta fronton is located just a hundred meters away, the last bastion of professional remonte fading but holding out somewhere between life and death.

If anything characterizes the Basque Country it is, on one hand, its language: Euskara. And, on the other, its bodily expressions: its indigenous games like pelota games that, as branches of a tree, have evolved with the passage of time. Remonte is one of those games.

The Galarreta fronton of Hernani (Gipuzkoa) full of people. | Photo: EL DIARIO VASCO

Brief History of Remonte

The type of pelota game known as remonte made its burst to courts at the beginning of the 20th century. It was in Pamplona (Navarre) when a glove player named Juan Moya devised the possibility of manufacturing a basket made of reed and chestnut rather than the ancestral glove, a pan shaped mitt, made of heavy, and costly bovine leather. That innovation led to a revolution in the game: the ball acquired a rapid speed when projected; that is, rather than throwing the ball by taking advantage of the short distance of the glove, with the new mitt, the ball came to a blistering speed after being forced all the way down the mitt, from the hand to the tip.

The reception by the glove-pelota players was excellent and the implementation was immediate. So from 1910 on, professional remonte festivals with betting take place in Pamplona (Navarre) and San Sebastian (Gipuzkoa). As with other forms of professional vocation, betting has allowed keeping the doors open at commercial frontons.

San Sebastian, in the late 19th century and early 20th, the summer capital of the Spanish Court and its capacity to draw the political class, facilitates the presence of large audiences in the different frontons of this city, either with hand ball players, pala, remonte or jai-alai.

Madrid, the capital of Spain, is home to various commercial frontons during the 19th and 20th centuries until at the end of the decade of the 60s and the time of splendor ending with the collapse of the Recoletos fronton and somewhat later the Madrid fronton. Barcelona, especially the last century, also welcomed several frontons where games of jai-alai, pala and racket were offered.

In 1968, when the Urumea fronton of San Sebastian officially closed its doors (there were several weekly features of remonte held) foreshadowing the disappearance of professional remonte after a trajectory of about fifty years.

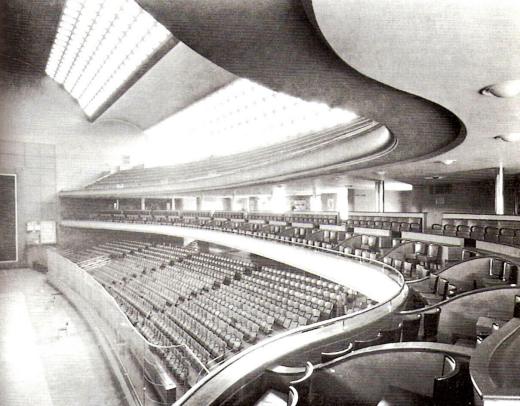

The historic Recoletos fronton in Madrid, inaugurated in 1936. The bombing of the Spanish Civil War deteriorated it. It never reopened.

However, two years later, the Galarreta fronton opened a new fronton in a rural area belonging to the town of Hernani (Gipuzkoa) located just a few kilometers from the capital, San Sebastian. An adventure promoted by some remonte fans who the journalist Francisco Ezquiaga described at that time as: “romantics of Orio”, after the coastal town of Gipuzkoa where they were from.

If there was reluctance because of the location of the fronton (on the urban periphery, quite unusual) it was an enormous success. There were sell-out crowds at the four weekly games. The 50 million pesetas that it cost to build the fronton were paid off in the first year. A line-up of 45 players made up the roster. The old Euskal Jai of Pamplona reopened and shortly after a new fronton opened in Huarte (Navarre).

However, following the dynamics of other commercial frontons of instrument-using games, the affluence of the public slowly fades and the activity is subject to a process of decline. With the beginning of the 21st century, Galarreta managers decide not to continue with the business and the remonte modality seems doomed to an end.

After closing for several months, a group comprised of several former remonte players assume management of the fronton, motivated mostly by emotional rather than rational reasons. Three years later, after trying to revitalize the fronton at all cost but unsuccessfully, they propose to the 28 pelota players a kind of cooperative in which the managers act as non-profit managers and allow the players to benefit from the profits based on the settlement of costs and revenue. The last shot at saving professional remonte.

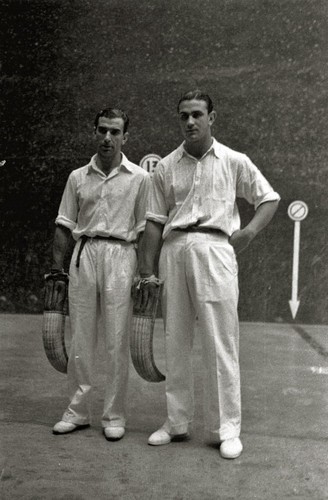

Abrego and Salsamendi at the 1944 championship. Two historic figures in this modality of Basque pelota. | Photo: wikipedia

The history of remonte and its future is not far from the various modalities of pelota like jai-alai, pala and racket. They all have a common link. They all had their time of splendor extending throughout almost all of the 20th century and now are all barely surviving, or have disappeared as in the case of the racket players.

Why are these frontons and their for-profit ball games doomed to disappearance or a symbolic existence?

A plausible explanation for the collapse of these modalities can be found in the ideas of Joseph Shumpeter, along with Keynes, one of the most influential economists of the 20th century.

Known as the “father” of innovation, Schumpeter describes five cases of innovation that lead to market changes:

1. The introduction of a new product.

2. The introduction of a new method of production or marketing of existing goods.

3. The opening of new markets.

4. The acquisition of new sources for raw materials.

5. The creation of a new monopoly.

Schumpeter calls this process creative destruction. In a nutshell: something new replaces the old, or in short, capitalism. In this whole process of change the main protagonist is the entrepreneurial innovator, an individual outside of the ordinary, an adventurous type, full of vitality and boundless energy. The entrepreneur creates markets for the inventions of geniuses, standing out by perseverance and ambition. The Schumpeterian entrepreneur (this new person) comes from any social class, dreaming of creating an empire, a dynasty.

Success, according to Schumpeter, creates imitators; successful people today may be losers tomorrow. When an entrepreneur creates a monopoly as a result of his or her innovations, it immediately generates hundreds of imitators. In the guidelines that support the Schumpeter theory we can find the answer to the dismantling that the world of the Basque professional pelota is experiencing, and not only in this industry, but in all areas.

Schematically, I will link the interpretation of Joseph Schumpeter with what has happened in jai-alai, pala, racket or even in what I see coming to professional hand ball.

Remonte is a spectacular modality. | Photo: EL DIARIO VASCO

First let´s look at the historical context in which the first businesses emerge: the end of 19th century, in the middle of 2nd Industrial Revolution, during a time of unprecedented innovation. The same is true for some modalities of Basque pelota. A transformation occurs from a rural game to urban, courts undergo radical change; from this time forward the game form of the future is “blé” (playing against the front façade).

It is at this time, somewhere between the 19th and the 20th century when jai-alai and remonte begin. The brilliant idea of Meltxor Guruzeaga (innovator of the basket as the playing instrument) and Juan Moya (inventor of the remonte) cause a revolution in the game.

During this period, the business figure and spirit of the entrepreneur emerges in the purest Schumpeter style contributing to the opening of frontons. Continuing with the above mentioned ideas of Schumpeter, these adventurers look for new markets, either in capitals of Spain or in various spots around the planet as in the case of jai-alai. Commercial frontons throughout much of the 20th century are synonymous with success. The product operates in a context of low competition (bull fights and theater) and in the industrial development in the case of Spain, the decade of the 1960s is characterized by GDP growth of around 7%.

One of the points exposed by Schumpeter, which is based on monopoly, we find at various times in the history of commercial pelota. First, when the forerunner of jai-alai, “punta-bolea”, is the Queen of Basque pelota. Its success (remember what Schumpeter says) causes the appearance of imitators. Frontons pop up hosting other modalities such as pala, remonte, and racket games.

The boom of pelota to jai-alai in the late 19th and early 20th centuries causes the expansion of this modality across continents. This phenomenon causes a labor shortage. The lack of jai-alai players and the need for labor leads to employers being forced to hire pala, remonte and racket players.

Put another way, the professional pelota boom was such that in the absence of major competition, except for bulls and theater, the pelota professional business resulted in a profitable one for a certain period, especially until the decade of the 60s in the 20th century.

Betting mediators are an essential element in all Basque pelota modalities. | Photo: EL DIARIO VASCO

Decadence

Professional pelota unfortunately and inevitably fulfills the Schumpeter hypothesis unequivocally. While Spanish society lives unprecedented sociological changes, professional pelota dependent on betting, is unable to innovate and dies from its success. Creative destruction, such merciless dynamism, a result of capitalism crushes the pelota world.

A graphic example of the process of creative destruction is what happened with the transformation of jai-alai in its beginning when someone had the brilliant idea of shifting to betting on competition, undoubtedly, an innovative change involving the re-launch of a modality already spectacular in its own right.

The North American experience of jai-alai reflects what Schumpeter so accurately predicted. For several decades jai-alai functioned with little competition in Florida, the betting world was restricted to horse racing, dog racing and jai-alai with each industry operating exclusively during separate seasons.

Success creates imitators, coupled with the eagerness to earn money through tax collection. Interest is generated and of it comes competition, lotteries, casinos, and Internet betting. Innovation in the world of betting is constant yet jai-alai remains static. There has to be someone to pay for it. Jai-alai ceases to be attractive to the betting consumer looking for higher yields on investments and the same happens to the business owner whose only aspiration is to maximize benefits. Creative destruction is relentless in the case of jai-alai. The betting world continues its course but has found more appealing places.

To make matters worse, business owners with the entrepreneurial spirit of the past have disappeared. New managers are insensitive to an industry with traditions of the past, linked to something bigger than just a way to make money. The Berenson dynasty in the USA; Aranzibia in the Basque Country; the “Romantics of Orio” who opened the Galarreta fronton. Entrepreneurs who took jai-alai to Orient lands, Africa, Asia, appear as legendary characters, anachronistic, unrepeatable; except a few honorable exceptions such as the businessman Aitor Totorika and his partner Alix on Philippine soil.

Creative destruction has been carried through to the golden age of pala, remonte, and jai-alai. The flames of innovation devastate not only in the pelota world but in the business world as well. New sprouts arise from the scorched earth. The health of an ecosystem is measured by its capacity for regeneration. Will the modalities of professional pelota be able to survive in a world of constant innovation?

I think so. I think your article will give those individuals a good showing. And they will convey thanks to you later